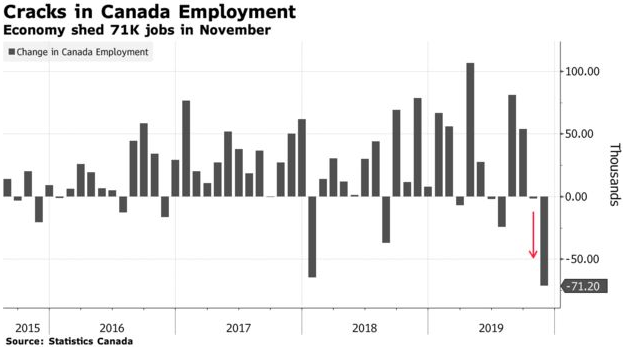

HUGE DECLINE IN JOBS IN NOVEMBER AS JOBLESS RATE SURGES

One month does not a trend make. Statistics Canada announced this morning that the country lost 71,200 jobs in November, the worst performance in a decade. What’s more, the details of the jobs report are no better than the headline. Full-time employment was down 38.4k, and the private sector shed 50.2k. The jobless rate also rose sharply, up four ticks (the most significant monthly jump since the recession), to 5.9%. Hours worked fell 0.3%, and remain an area of persistent disappointment—they’re now up just 0.25% y/y, much more muted than the 1.6% annual job gain.

One month does not a trend make. Statistics Canada announced this morning that the country lost 71,200 jobs in November, the worst performance in a decade. What’s more, the details of the jobs report are no better than the headline. Full-time employment was down 38.4k, and the private sector shed 50.2k. The jobless rate also rose sharply, up four ticks (the most significant monthly jump since the recession), to 5.9%. Hours worked fell 0.3%, and remain an area of persistent disappointment—they’re now up just 0.25% y/y, much more muted than the 1.6% annual job gain.

The one area of strength was wages, with growth accelerating to match a cycle high at 4.5% y/y. But wages tend to lag the labour market cycle, so if this weakness is the start of something bigger, wages gains are likely to slow.

The monthly moves were soft, no matter how you slice them. Both full-time (-38.4k) and part-time employment (-32.8k) were down. Similarly, private sector employment (-50.2k) led the way, but self-employment (-18.7k) and the public sector (-2.3k) also saw net losses.

Until last month, we saw a long string of robust job reports in what is usually a very volatile data series, so a correction is not surprising. But this report appears to be more than a statistical quirk and belies the Bank of Canada’s statements this week that the Canadian economy remains resilient. Employment is still up 26k per month in 2019 to date consistent with a 1.6% y/y gain, and most of that comes from full-time work. And some of the drop in November reflected a decline in public administration jobs retracing October’s gain that might have been related to the federal election. Nevertheless, the 0.4 percentage point uptick in the jobless rate is the largest since the financial crisis in early 2009, and manufacturing jobs were down more than 50k over the past two months.

By industry, job declines were widespread in the month, with only 5 of 16 major sectors posting improvement. Net losses were shared across both the goods and service sectors. Manufacturing (-27.5k) shed jobs for a second month, and notable declines were seen in public administration (-24.9k, likely a reflection of post-election adjustment) and accommodation and food services (-11k).

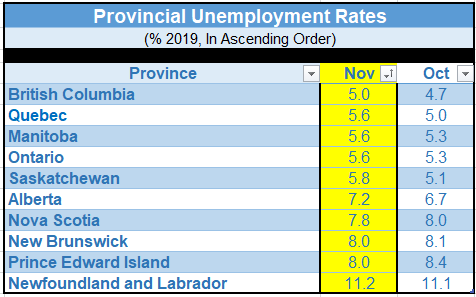

By region, Ontario and PEI were the only provinces to manage job growth last month, with all others deeply in the red. Quebec stands out, shedding 45.1k net positions in a second monthly employment decline and pushing the unemployment up to 5.6% (from 5.0%; the largest monthly increase in nearly eight years). Quebec’s jobless rate is now equivalent to that in Ontario. Things were not much better out west: Alberta and B.C. both lost 18.2k net positions. In the case of the former, this was enough to send the unemployment rate up half a point, to 7.2%. Ontario bucked the trend, adding 15.4k net positions, just shy of erasing the prior month’s drop. Still, the unemployment rate in the province rose to 5.3% (from 5.0%), as more people joined the labour force. (See the table below.)

Job growth slowed in the second half of this year. Over that period, the average monthly job gain has been a paltry 5.9k compared to an average monthly gain of 24.4k over the past year. For private sector employment, the equivalent figure flipped into negative territory (-4.3k) for the first time in more than a year.

Bottom Line: Today’s report means that the Bank of Canada will be keeping an even more watchful eye on the jobs report. The year-on-year pace of net hiring has decelerated for three straight months now, driven in large part by a slowing pace of private-sector hiring. It seems a safe bet that even if we see some recovery in the coming months, the substantial gains of recent years are unlikely to be repeated.

The Bank of Canada has been emphasizing Canada’s economic resilience in its recent communications. One month of soft jobs data will hardly break that narrative, but coming after a modest October, it is not hard to imagine a hair more worry about the durability of growth. The bigger question is whether this weakness persists, and more importantly if it feeds into consumer spending behaviour and housing activity, the Bank’s key bellwethers.

We continue to believe that the BoC will cut rates in 2020, owing mainly to Canada’s vulnerability to trade uncertainty. The loonie sold off sharply on the employment news, particularly so because of the stronger-than-expected labour market report released this morning in the US.